SALLE 0.1

Picalso

2019. First rendezvous and proposal for occupying the Musée Picasso in 2023, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the artist’s death. Without HIM, if I prefer. My mother’s words wend their way in, imposture syndrome in their wake. At an opening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, upon seeing my works between those of Hopper and Magritte, she exclaimed: “You really fooled them!” This time, I imagine her whispering, “Why you?”

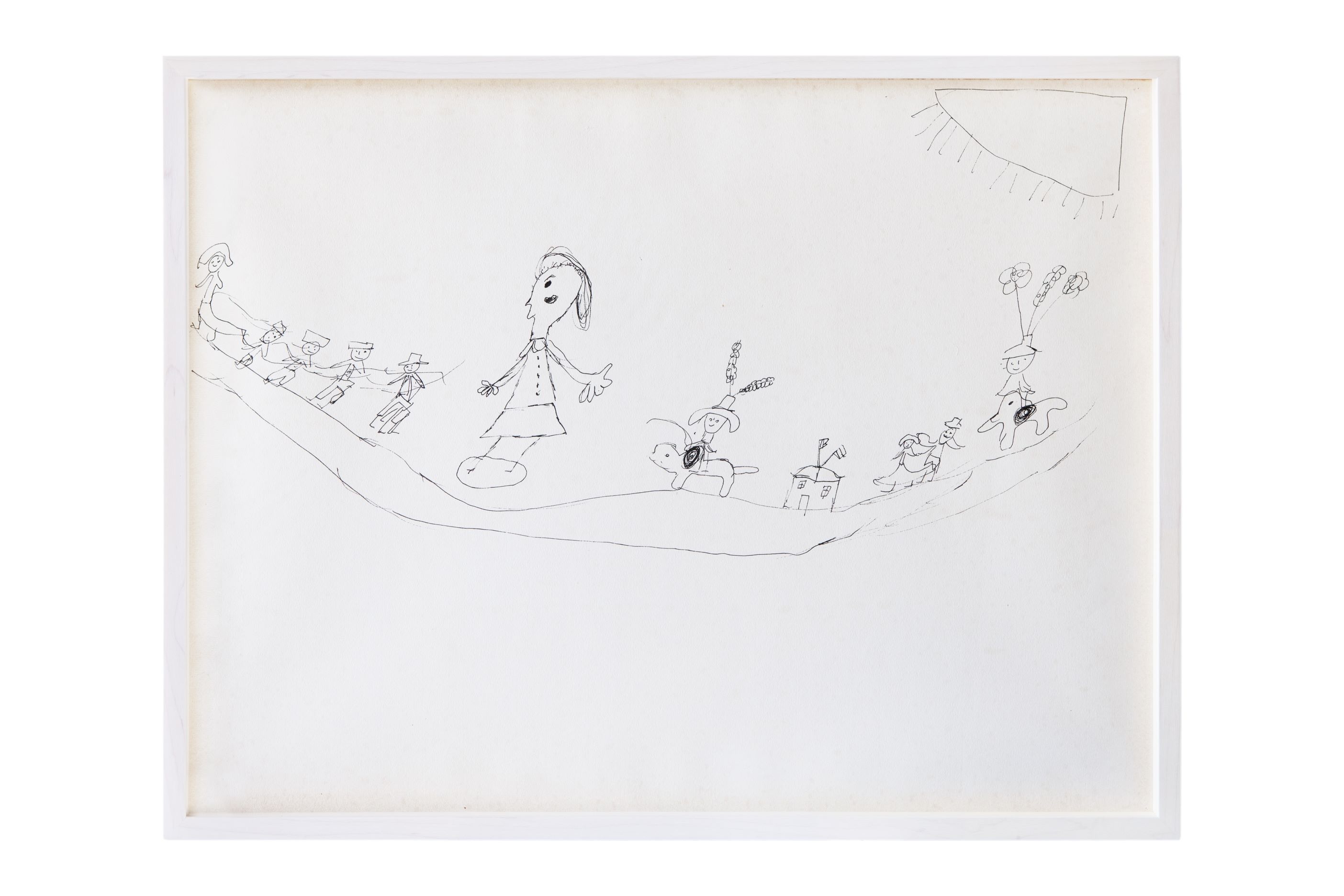

Let’s recap. There’s my very first work, or at least the one my father gave that status to by framing it and retraced the caption penciled on the back which had faded. I was maybe six years old, and this drawing made my grandmother say that there was a Picasso in the family. There’s Tête, a Picasso stolen from Chicago, whose composite portrait I’d made from the recollections of those who’d known it. There’s Prolongation, the title of one of his exhibitions in Avignon, which I promised myself I’d borrow one day. It’s thin.

Drawing layout

1. At first I wanted to make a statue and then I decided to make. a general who would be represented by the statue

2. Then I made a bride in front of the statue and four figures to carry the bride’s train

3. behind the statue I drew a horseman

4. behind the horseman the general’s house

5. behind the house: a betrothed couple

6. and lastly another horseman Sophie

SALLE 0.2

It should be possible to show the paintings that are underneath the painting. Pablo Picasso

Picassos in lockdown

Second rendezvous at the Musée Picasso, during the lockdown. No visitors. The Picassos were under protection, wrapped up, hidden. Underneath—a ghost-like, less intimidating presence that I immediately photographed. Even before I knew it, I had accepted.

SALLE 0.3

Guernica

I learned from a book by Mary Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, that after seeing Guernica for the first time at MoMA in New York, Gorky had called a meeting at De Kooning’s 22nd Street loft. A dozen artists listened as he conceded: “We have to admit, we are bankrupt. So, what I think we should do is try to do a composite painting… In this room, one of us can draw better than the other, one has a better sense of color, one has a better sense of ideas… We should pick a general topic and then all go home and the next time we meet, we all bring our version of [that topic].” Each artist had to rise to the challenge laid down by Picasso alone. Lee Krasner said: “I don’t think I remember a second meeting on it.” I’m not part of a group. I didn’t try to convene a first meeting. I chose instead to spread out over 27.0824 square meters—the surface of Guernica—the talents of the artists who occupy the walls of my home. My collection of photographs, miniatures, works inherited from my father… 7.76 × 3.49 meters of drawing by Francis Alÿs, Annette Messager, Markus Raetz, Tatiana Trouvé, paintings by Bernard Frize, Damien Hirst, ideas by Maurizio Cattelan, Bertrand Lavier, sculpture by Laurie Anderson, Serena Carone, Elmgreen & Dragset, Robert Gober, Jean-Michel Othoniel, photography by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Diane Arbus, Raymond Depardon, Dennis Hopper, Cindy Sherman, pain by Alex Majoli, afición by Miquel Barceló, disappearance by Christian Boltanski, the unspeakable by Marie Cool Fabio Balducci, elsewhere by David Rochline…

SALLE 0.4

A Musée Picasso without Picasso. Or almost.

SALLE 0.5

Contend with absent paintings.

Begin with the most invisible of all: Pigeon with Green Peas, swiped from the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2010, and probably destroyed. I read in the newspaper that the thief had taken three works that were not part of the job, because he liked them. He was behind bars; I wrote him. He replied that he found the little Matisse exceptional, then Modigliani for its beauty, the Braque perfectly executed, the Léger snazzy. But he wasn’t a fan of Picasso. Wrong turn

Phantom Picassos

Paul Drawing, Man with a Pipe, Swimming Woman, The Death of Casagemas and Bather with a Book were missing due to being on loan. I asked the curators, guards, and other museum staff to describe them to me. When they returned, I veiled them in the memories they leave behind in their absence.

The Death of Casagemas

We’re looking at a very small painting, a close-up of a man’s head, in profile, lit by a candle, eyes closed, a bullet mark on the right temple. But it’s not a bleak picture, there’s yellow, red, something contradictory. Like a black sun. We’re face-to-face with a man abandoned by life, we don’t see death, we see the dead. There’s no mistaking it, not even in the tilt of the face, the cadaverous lividity, you feel a kind of vertigo, you’re in the painting. We see the silence. The light is evanescent, like a counterpoint to this extinguished face. A peaceful painting, really. This is not a sleeping man. We see a corpse with a sort of orifice, a stain on the forehead, dried blood, a green color, the color of death. Acid, cold, neither peaceful nor reassuring. It must be about 30 cm by 40, it doesn’t take up much space and yet doesn’t go unnoticed. It’s like a Christ figure. When I visit his floor, I never turn away. Vibrant, powerful, brilliant, a kind of fireworks display of raw colors. Its fierceness comes from the color palette. It’s a painting that tells the sentimental story of the suicide of a close and dear friend. We feel sadness, grief, and the memory of a dazzling life. We see a depiction of death. It’s a faithful description of Casagemas, who, after trying to kill the woman who wanted to leave him, shot himself in the head. I’ve seen actual dead people, they look like that, that expression of nothingness, neutrality, emptiness. They were the same age, had moved to Paris to become artists, and their paths diverged. Casagemas chose to end his life when Picasso went towards the light. It’s 1901, just before his blue period, and Picasso is trying to make a name for himself by painting in the style of… He’s immersed himself in the avant-garde of the time and already had the ability to seize on everything around him. Even if it’s called The Death of Casagemas, that’s fine, but it’s only a title, so don’t disregard the painting. When you’ve got nothing to say about a painting, you tell the story, but if the guy killed himself because his mistress rejected him, who cares!? Novelists are interested in that, not painters. Here’s a guy who tries everything: impressionism, futurism, pointillism… And then he must have said to himself that he wasn’t Van Gogh, and he was right. I didn’t know anything about the backstory and it still spoke to me. It’s rare to see a close-up of a suicide victim’s face. This one’s not deformed; no grimaces or dripping blood, rather like “Le Dormeur du val” (The Sleeper in the Vale). Picasso often tries to twist things, but in this case he didn’t try to do too much, a “no fuss” feel. It’s a work that Picasso kept for himself, never showing it. You can feel the affection, the contemplation, as if he had tried to protect him. This farewell is clearly a means of exorcizing. Not unpleasant. Many visitors don’t see the death unless they’re told it’s there, because it’s almost joyful. Posthumous portraits are often sallow, pale; here, the colors sparkle. The candle is not secondary, it tells us that the best is yet to come. It leaves me cold; I find it kitsch. It’s often discussed ad infinitum, but let’s settle down, folks. It’s a severed head lit by a little candle. The man’s complexion is quite green, he doesn’t look well to me, he’s dead. The person’s eyes are closed, he’s sleeping peacefully, his facial expression is serene. We can’t feel death, but we know it’s there. In terms of veneer, he’s doing well—if you can say that about a dead man. It’s a pivotal work, important for talking about the evolution of the style, the transition to his blue period tortured, a period that the public really loves; so it’s often lent out, it travels miles! I’m watchful of it. If we’re talking safety, we’re talking a dangerous size, easy to filch. But if anyone touched Casagemas, I’d be very angry. He needs to be at peace, he should be left alone. Just a portrait, unexpressive, loveless, cold. I was going to say: he’s dead, but really dead in the sense that nothing comes from him anymore. I find it very… very dead. I can’t pass this man on his funeral bed without giving him a nod. I don’t know what he’s telling me, but I want to sit by his bedside and watch over him. I’ve never spoken to him, but I’ll have to give it a try.

Bather with a Book

A being with round shapes and a mineral appearance occupies most of the canvas. It’s a female figure, hunched over herself, completely naked, a book open on her knee, absorbed in her reading, pensive, not present to the viewer’s gaze. Were she to unfold, she wouldn’t fit in the painting. An enormous shell unfolds in space. She’s naked and engaged in a book, head down, hand resting on her elbow. She takes up three quarters of the surface. She holds a melancholic pose, seems captivated, and it’s hard to tell what she’s reading—probably a sad story. In the background, an icy blue, a touch of violet, a play between horizon, sky, and sea. The tone is cool. The texture is powdery, the tones soft; I find it delicate and contemplative. When I pass in front of her, I slow down. She’s my sweetheart, if I do say so. It’s a bather, instantly recognizable as a Picasso. Serenity, harmony, distance from the world; we can speak of inner light. We let ourselves be transported; we’re at the seaside, the sun is setting. She’s scary. Her body is reduced to a pile of bones. The character is austere, hard, reflecting the violence of Picasso’s mind at this time. Luminous. It belongs to a fundamental period, that of the famous Guernica and the weeping women, but that’s not what this is about. It’s more of a continuation of what he did in the 1930s, deconstruction of shapes, metamorphosis of the human body. She’s from 1937, 130 cm high, 97 cm wide, huddled over herself, meditative. She’s reading, but I don’t see a book. Neither clothed nor nude, rather a block of stone. A woman with no expression, a stranger, reads an invisible book. There’s certainly black, gray, lots of blue, a little pink or ochre, but it’s almost a monochrome, this thing. Some works allow you to draw conclusions, but not this one. She’s a woman, with some easyon-the-eye attributes. She is an invitation to a certain kind of escape. There’s a face in the middle, very small and disproportionate. A nose, eyes, a mouth, eyebrows, and very far away, an ear, like the features found on stones. I see two faces, face-to-face. And beneath this right hand, where is her breast? Rounded shapes, femininity, bent-over posture that I feel as a softness, but cold colors in blue-grey that may evoke the dark times on the horizon. I look at her from a technical point of view. Three times a day, I check off her presence. So, I look at her, but I forget her. I’ve known her for twenty-four years, I see her regularly; massive and sculptural, she reminds me of those bunkers you find by the sea on the great cold beaches of the North. She’s a big girl, she’s not threatened, she’s not going to leave on someone’s arm. She doesn’t have an assigned seat, as someone would have at a table, but she’s often on the landing, and visitors photograph the staircase, almost pressing themselves up against this crouching woman, as if she didn’t exist. Yet she’s used to being looked at. But do we look at works of art in a museum? We see a sort of huddled, stone-colored ghost, seated cross-legged, who has been likened to Rodin’s The Thinker because she’s thinking, or at least reading. An abstract book, geometric, lines. It’s not impastoed, you can see the weave of the canvas, the materials give themselves away, and when you get close, the color vibrates, you can see the artist’s hand. She is upright, only her head is tilted towards the open book in her lap, but it’s not a reading position, it’s a painter’s perspective. Charcoal, oil paint, pastel. Shadows on the body, the lines of words, the face, everything black is outlined in charcoal, then the paint comes on, and at the last moment Picasso applies chalk or pastel, hence its mineral character. I know her well, I don’t need to look at her anymore. I try to see her, but I can’t. A woman on her knees reading, the subject is distressingly banal. At least Manet’s Mallarmé is of a writer reading his texts. She is velvety, soothing. When I saw her unframed, unprotected, I wanted to sit beside her to look at her calmly, but she was immediately transferred to a recumbent position for the reattachment procedure. I was alone with her, I saw what others don’t, I put my hands on her. The pastel in the blue background gives her a velvety look, the medium takes you on a journey through the work, around the shapes, a feeling of well-being, of fullness, something dazzling. The sky is limpid, the sea flat, the atmosphere serene and the woman motionless. Nothing happening. No signature. No gilding. A typical white American box. And since she’s often on the landing, the question we’re most asked in front of it is: “Where’s the exit?

Next floor : link